APIs with Swagger, Swashbuckle and NSwag

APIs are a great way to write and centralize logic especially if there is any intention of having this be used in a multi-channel aspect. But, at least in my experience, there are always a small handful of pitfalls:

- Discovery of endpoints

- Having to dig around and find a list of the available endpoints

- Documentation of the endpoints

- What the endpoints actually do, their inputs and ultimately their outputs

- Invoking and mapping the result of these API calls from within the client framework

- This usually let me spinning up a service, hand rolling some type of

HttpClientcall, and then deserializing the data into proper objects or models

- This usually let me spinning up a service, hand rolling some type of

All of that was until I was introduced to Swashbuckle and its counterpart, Swagger.

Great, a tool that not only defines and helps enforce an API standard (OpenAPI) but also facilitates testing it! That effectively knocks out the first two bullets on my “complaints” list. That last one is kind of a kicker though, but then after digging a little NSwag rose to the top. Gamechanger, at least in my book. Not only does it help generate a .json/.nswag file that defines the entire API, but it also helps generate correlating classes in CSharp or TypeScript from that same file. Never thought someone could be excited about working with APIs… but here we are.

We should probably lay the context a little for our particular scenario, the high level project is as follows:

- An API framework (.Net 4.6ish to leverage some necessary libraries, API App in Azure)

- A MVC Site that will consume the API (dotnet core Web App in Azure)

- Future: Mobile App

- Far Future: 3rd party API consumption (leveraging Azure API Management)

So as you can see, need something that can be used by an MVC site, a Mobile app and eventually play nice with Azure API management.

OK, enough of how we got here, let’s walk thru some of the moving pieces that it took to get all the things working:

API Project

This project is your run-of-the-mill ASP.NET Web Application -> WebAPI project with the following references:

That gets us Swagger the ability to generate the myApi.json doc to use as a data-contract of sorts between the API and the MVC project.

Upon including Swashbuckle you should now have an App_Start folder with a SwaggerConfig.cs file in it. Crack it open and you will see an onslaught of goodies that range from allowing Basic/OAuth to including comments at the endpoint level (which we certainly want in this case):

SwaggerConfig.cs

public class SwaggerConfig

{

public static void Register()

{

var thisAssembly = typeof(SwaggerConfig).Assembly;

GlobalConfiguration.Configuration

.EnableSwagger(c =>

{

// your current version of the API and title

c.SingleApiVersion("v1", "My.API");

c.PrettyPrint();

// generate a comment xml doc to feed into the swagger doc

var xmlFile = string.Format("bin/{0}.xml", Assembly.GetExecutingAssembly().GetName().Name);

var xmlPath = Path.Combine(AppContext.BaseDirectory, xmlFile);

c.IncludeXmlComments(xmlPath);

})

// enable the incredibly handy SwaggerUI

.EnableSwaggerUi(c =>

{

c.DocumentTitle("My API");

});

}

}

The above snippet is very simple: it leverages the comment xml file created on build (Project Properties -> Build tab -> Xml Documentation File) and it enables the Swagger UI (at https://localhost:XXXXX/swagger/ui/index.html).

Now, let’s create a controller:

AccountController.cs

[RoutePrefix("api/Accounts")]

public class AccountsController : ApiController

{

/// <summary>

/// Get an account by ID

/// </summary>

/// <param name="accountId"></param>

/// <returns></returns>

[HttpGet]

[Route("{accountId}")]

public Models.Account Get(Guid accountId)

{

var accountToReturn = _accountService.Get(accountId);

return accountToReturn;

}

}

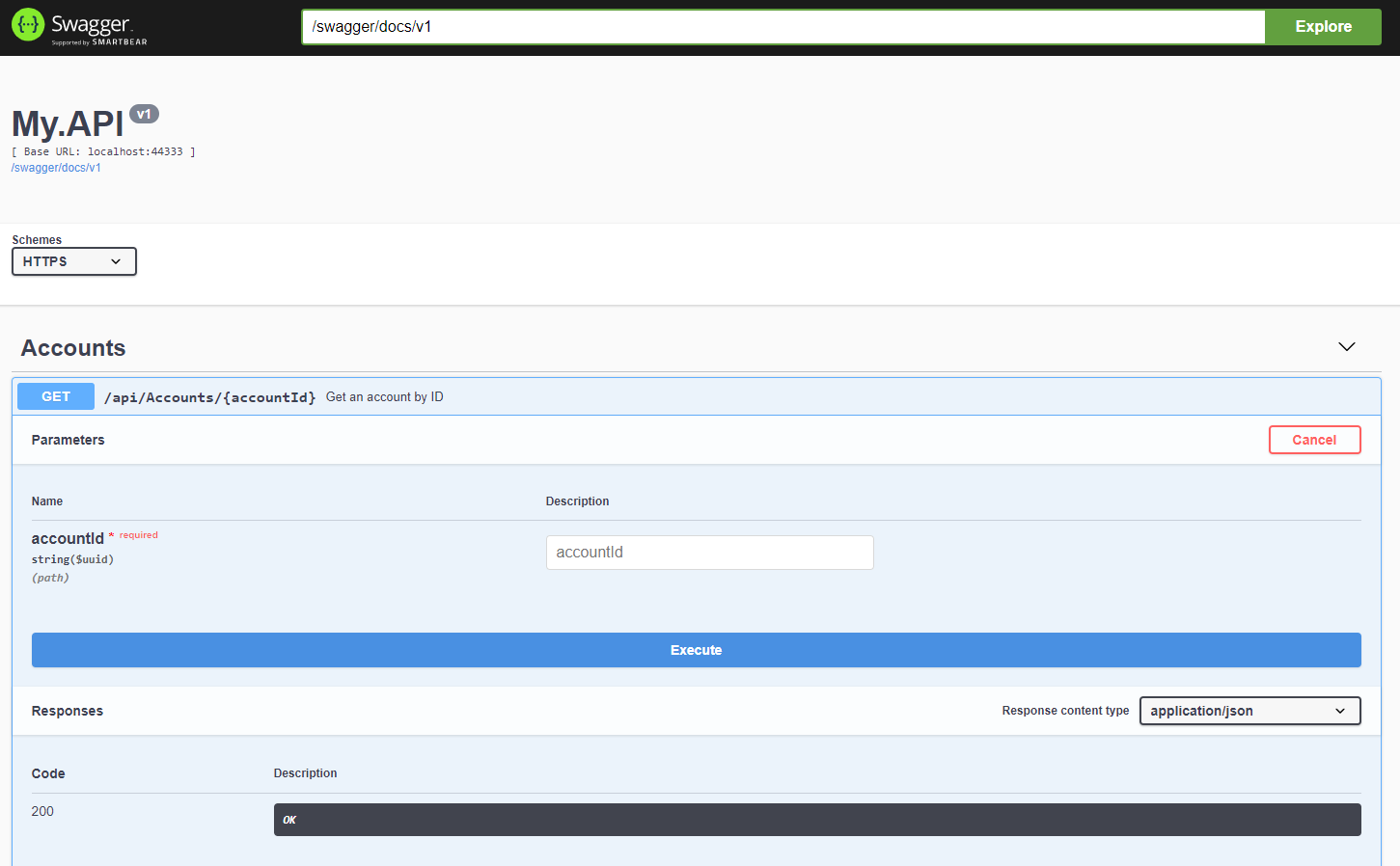

Sweet, everything compiled because we actually have an _accountService already defined and it’s not fake for the purpose of this post! Let’s run this project and pull up https://localhost:XXXXX/swagger/ui/index.html:

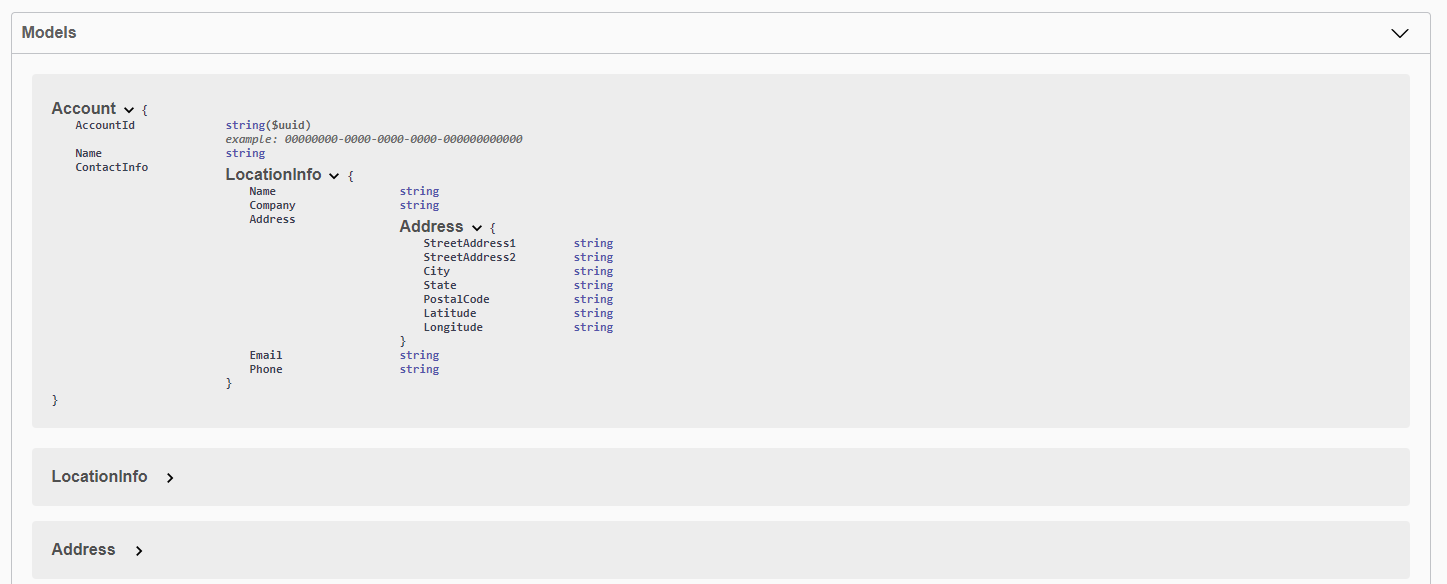

There it is, an endpoint with input, output and comments. Navigating a little further down we can even see the models returned thru the endpoint:

Tremendously helpful when trying to validate all the working things. Now that we have a functioning API let’s turn our attention back to NSWag and get this thing consumable to our MVC project. This part was just a hair more manual, but within the MyApi.csproj xml itself, scroll way to the bottom and add the following right before the </project> element:

After Build Swagger Doc Creation

<Target Name="NSwag" AfterTargets="Build">

<Exec Command="$(NSwagExe) webapi2swagger /assembly:bin/My.API.dll /output:my.api.json" />

</Target>

This creates a proper OpenAPI doc:

{

"x-generator": "NSwag v12.3.1.0 (NJsonSchema v9.14.1.0 (Newtonsoft.Json v11.0.0.0))",

"swagger": "2.0",

"info": {

"title": "My Title",

"version": "1.0.0"

},

"consumes": [

"application/json"

],

"produces": [

"application/json"

],

"paths": {

"/api/Accounts/{accountId}": {

"get": {

"tags": [

"Accounts"

],

"summary": "Get an account by ID",

...

Great! Now, to make our lives easier, our MVC project is within the same greater directory, but just within a different folder (a sibling folder to our MyApi/ folder). Since we will have line of sight to it, assuming the project folder names won’t change any time soon, we can start knocking out some of the MVC project pieces.

MVC Project

The MVC project itself is a dotnet core 2.2 project but all the API calls will take place within a dotnet core 2.2 class library project. This Services project has the following references:

To be clear both of these projects have plenty of other references, but these are the ones I wanted to focus on since the rest are ancillary to the work being done, not so much the data binding between the API and MVC projects. Now that we have NSwag.MSBuild and NSwag.CodeGeneration.CSharp included, we can knock out the remaining pieces. Let’s start by adding a BeforeCompile:

Before Compile API Code Generation

<Target Name="NSwag" BeforeTargets="Compile">

<Exec Command="$(NSwagExe_Core22) swagger2csclient /input:../../My.API/My.API/my.api.json /namespace:My.MVC.Services.Classes.DataAccess /ClientBaseClass:ApiClientBase /GenerateBaseUrlProperty:false /UseHttpRequestMessageCreationMethod:true /UseHttpClientCreationMethod:true /InjectHttpClient:false /UseBaseUrl:false /output:Classes/DataAccess/ApiClient.Generated.cs" />

</Target>

As you can see from the Command we are doing a few things here (all documented here):

- input: relative path to the

.jsonfile created by the API project - namespace: the location within the project and namespace of the generated class

- clientbaseclass: a custom defined base class that the generaged class can inherit (will elaborate below)

- generatebaseurlproperty: with this set to true, you need to pass in the API url on your client calls

- usehttprequestmessagecreationmethod: call the

CreateHttpRequestMessageAsyncon the base class - usehttpclientcreationmethod: call the

CreateHttpClientAsyncfrom the base class - injecthttpclient: if set to true the httpclient lifetime needs to be externally handled

- usebaseurl: if set to true the out-of-box

BaseUrlis used and exposed - output: the actual generaged class

Now that we covered all the flags, below is the custom ApiClientBase with inline comments to help you understand why some of the flags were set:

ApiClientBase.cs

public abstract class ApiClientBase

{

private IHttpContextAccessor _httpContextAccessor;

public void SetContext(IHttpContextAccessor httpContextAccessor)

{

// _httpContextAccessor called in the _generateBearerToken

_httpContextAccessor = httpContextAccessor;

}

private string _bearerToken = "";

public string BearerToken

{

get

{

if (_bearerToken == null || _bearerToken == "")

{

_bearerToken = _generateBearerToken();

}

return _bearerToken;

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Custom CreateHttpClient so we can force the base URL from the appSettings rather than feed it in thru the client calls

/// </summary>

/// <param name="cancellationToken"></param>

/// <returns></returns>

protected async Task<HttpClient> CreateHttpClientAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var client = new HttpClient();

var apiSettings = new ApiSettings();

client.BaseAddress = new Uri(StaticApiSettings.BaseUrl);

return client;

}

/// <summary>

/// Creates a custom request message that adds the BearerToken to the header for identification purposes

/// </summary>

/// <param name="cancellationToken"></param>

/// <returns></returns>

protected Task<HttpRequestMessage> CreateHttpRequestMessageAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var msg = new HttpRequestMessage();

msg.Headers.Authorization = new AuthenticationHeaderValue("Bearer", BearerToken);

return Task.FromResult(msg);

}

}

Creating the ApiClientBase above, we are able to vastly simplify the client calls to the API:

AccountService.cs

public class AccountService

{

private IHttpContextAccessor _httpContextAccessor;

private AccountsClient _accountService;

public AccountService(IHttpContextAccessor httpContextAccessor)

{

_httpContextAccessor = httpContextAccessor;

_accountService = new AccountsClient();

_accountService.SetContext(_httpContextAccessor);

}

public async Task<Account> GetCurrentAccount()

{

var accountId = _httpContextAccessor.HttpContext.Session.Get("accountId").ToString();

var currentAccount = await _accountService.GetAsync(new Guid(accountId));

return currentAccount;

}

}

In the above snippet, the _accountService.GetAsync() call is from the generated ApiClient.Generated.cs and is handling the call to the API.

From this point on the rest is up to you!

There is a very good chance nothing said here is new, but if anything maybe just illustrating how some of the pieces above come together can help someone who might be stuck.

</message>